Whether it is a trend or a personal experience, but with the rare exception of the 68 Internationales Filmfestival Mannhaim-Heidelberg program presented as variations on the theme of parent-child relationships. It is especially important to note that sincere films are not so much about problems, but about awareness and unity of generations.

Of course, they are about love and forgiveness. The Asian region films, which give a considerable amount of interpretation and reflection on the theme of fathers and children, were particularly impressive in terms of cinematic discovery. I would like to present the analyze of some distinct authentic films below.

The swing maker (director Da Xiong) is specific as an illustration for its artistic interpretation rather than for reflection of a parent-children topic. The story itself tells how Liu, being a worker, simply builds a swing. The image of the swing itself refers not only to the metaphor of swaying time, but also to a kind of effect of the repetitive and cyclical movement of a person in the time.

The aesthetics of black and white make it both an off-context and a kind of documentary style that tells the «here right now» story. Broken dialogues, intersecting with contemplative landscape frames continue to work in the mind of the viewer, compiling a syntactical connection of the documentary-parable type. The camera resembles the aesthetics of Tokyo Story by Ozu. But does the frame work stylistically precisely in the context of this manner of storytelling? Yes, only from the parable figures of the characters in the compositionally similar structure of the frame, the characters of the Chinese film turn into revived images of the present. “A life caught unawares” transforms into life between the lines. Like the psychological features of human perception, the structure of the film from the general narrative of the story and the history of the relationship between the hard worker father and his family is built into a mosaic of impressions and captured moments of life of the main characters.

Thematically, the film narratively indicates to the viewer the problematic points of the relationship between the past (parents) and the present (young girls). It is important to note here that a double generational conflict unfolds in the context of the story: in the relationship between the daughter and the father, and in the hypothetical relationship between the daughter and her unborn child. In addition, a conflict of moral values, which sprout in a young girl, with the tenets of the surrounding society, focusing on money, is interestingly presented. Here, the swings appear as a multi-tasking symbol, which is both part of the image of the main character (i.e. the actual element of the story), and a way of metaphorical statement about the essence of life swinging back and forth.

The Taiwanese film Ohong Village (director Lungyin Lim), which takes a breathing film image and also documentary as the basis of its aesthetics, brings us back to the theme of the revival of traditions and understanding of cultural roots. However, the dominant one in this story is not the narrative, but the stylistic ways of transplanting a simple story onto the screen. Here the director uses another facet of documentary film — observation.

The main thing that allows us to spy on the characters of Sheng-Zhi and his friend Kuhn — is the camera. From time to time, peering into the seemingly ridiculous situations and decisions of the heroes, like trying to cling to a true life, the opportunity to understand it, from a rational and objective one, camera turns into something inexplicable and emotional. The poetics of moments can be seen in the frames where heroes are reflecting on life, especially where the father of Sheng-Zhi cultivating the tree of the ancestor. All the surrounding protagonists aesthetics of poverty and neglect — this is the narrative reality. In the plot structure, with the rare exception of unambiguous peripeteias (such as the crisis of a family business, a home quarrel, beating Kuhn, his father’s illness), there is no growing conflict, as there is no conflict at all. There is only the lifetime, which is comparable to the water surface of the sea surrounding the heroes.

The symbols in the film are highlighted and articulated. The tree that the hero is trying to hold during the storm definitely sets a key thematic line — and, yes, also the story of returning home. This means thinking about their own origins. The transformation of the hero is also obvious, which from an alien «overseas» white collar comes to the image of the sedate owner of a marine oyster farm. This one, in terms of plastic and image, associates with the father of the hero. Here it is — the power of combining tradition and youth. Enterprise of Sheng-Zhi, Kuhn’s tourist business, along with the good fortune and prediction of the gods lead to success. Everything comes on track in the unstable world of the prodigal son.

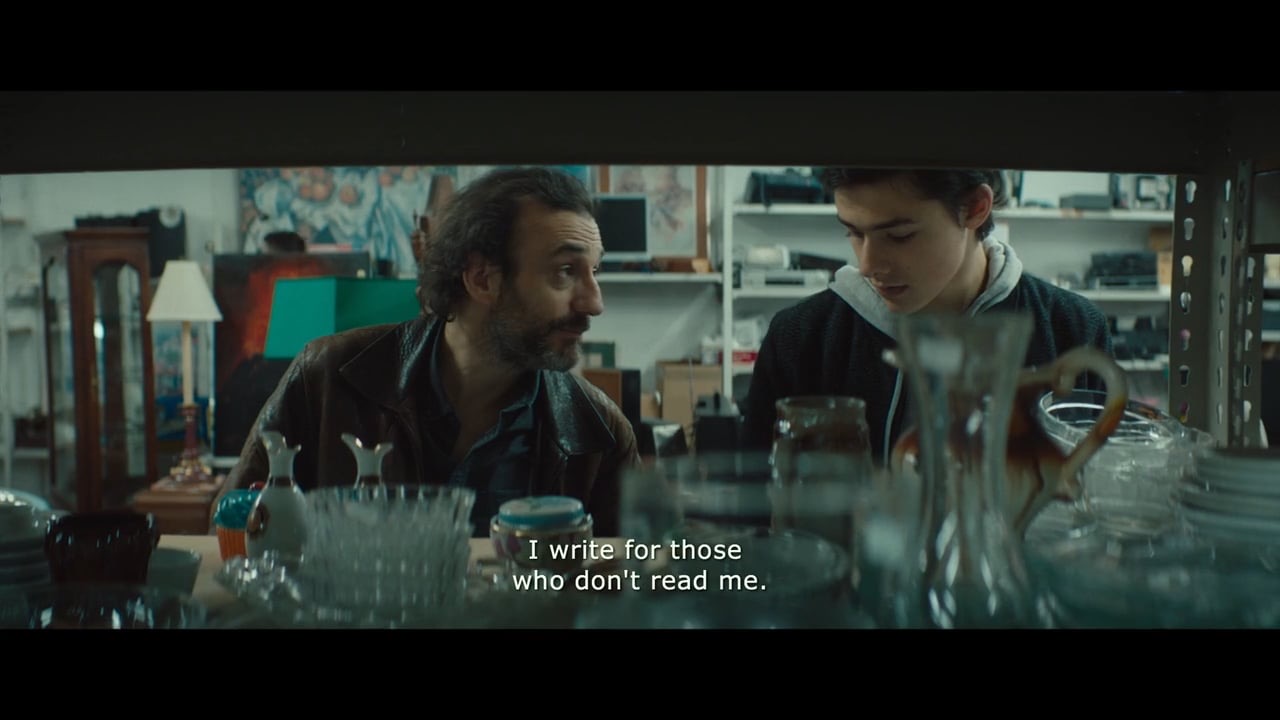

One of the most touching and poetic films of the filmfestival program was a Canadian film For those who don’t read me (director Yan Giroux). This story of the unrecognized genius of poetry and a boy just starting his career in art is by no means a narrative about the relationship between father and son. This is a story about great friendship and freedom, about the love of life.

Structurally, the film is built on two pillars: literature (word) and cinematography (movement). Literary origin is primarily due to the activity of the main character — the poet Yves. The hero’s exposition reveals a clear literary dominance. In fact, the viewer sees the hero for the first time when he took to the stage of the poetic evening in the bar. Here, Yves clearly defines himself with a word, that is a poem. The second character — schoolboy Mark, we see through the prism of everyday activities: in school, in communication with his father, which clearly hints at a greater degree of alienation between them. The age, social, and behavioral differences between Yves and Mark are formed in a very harmonious structure of the plot, as a linear narrative. Mark’s mother, Diane — beloved of Yves, becomes a kind of bridge between two men, between growing up and mature personalities. Constant verbal pronunciation of creative and personal freedom ideas for the first time enters into a symbolic figurative connection in one of the key points of Yves character development — in the scene of a running dog, dragging his own box on a chain. It is here that a complex poetic and at the same time psychological image is modeled, which poses a direct question to the viewer: can art or the person who is engaged in it be free at all?

And if the poet is characterized by verbal symbols, that is, poetry itself, then Mark is the embodiment of cinematic images. He’s more silent, he films almost all the time. The phone which was gifted by his father is nothing but a way of entertainment to the viewer. Meanwhile, the interaction between the heroes is classically unfolding. Yves moves in with Mark’s mother, and Mark begins to look at the unusual behavior of Yves. Gradually, he finds a lot of things attractive, and tries on the image of a freethinker poet along with Yves’s jacket. Parallel to Yves, who is writing a new poetry collection, Mark creates his own chronicle, comprehends his freedom, finds other ways of understanding life. But the most important thing is that he gets attached to Yves: as a father, as a creator, as a man. Each of the men seeks for themselves, their own ways. Each of them is growing and experiencing its own crises. But both also come to the true freedom of creation — to understand the beauty and art of life. The outcome of the film is the apotheosis of cinematic poetics. The allegorical nature of the image and frames of the film-dedication from Mark to Yves is recognition and gratitude, it is a great love. And, yes, it’s important that they read each other.

Under the Turquoise Sky (director KENTARO) is definitely the most cinematic and elegant film of the program also carries the issues of family values and the importance of returning to the roots. The story of the journey of the young and wealthy Japanese guy Takeshi to Mongolia is so absurd and fascinating at the same time that it captivates with its lightness and unique beauty.

Everything is perfect here: from the ordinary form of road-movie to non-trivial artistic decisions. But above all, the neatness and admiring irony with which the author approaches the display of traditions is so pleasant. Despite the fact that the film combines a synthesis of genres, it cannot be said that the picture is segmented. KENTARO seems to create a large patchwork multicultural blanket, sometimes stitching out fragments of eastern and western stylistic directions of cinema. The author’s lightness in relation to history is especially enjoyable. Pretty dramatic, it could become either radically authorial or frankly massive. However, the balance that the director maintains allowed the film to become as balanced as possible, while preserving an understandable and integral artistic concept. The comic-absurd part looks easy and unconstrained when the Mongol Amraa, in his dreams, steals his beloved from the wedding. The French flavor and style not only explain the dreamy nature of the episode, but also are a kind of irony over the cliché of love scenes. But this irony is not evil, but kind and with love. In general, the act of theft (of a horse in the plot of history, of a girl from a wedding) is a peculiar way of liberation. Here, the footage of Amraa riding a horse resembles the character of another Turkic film, The Centaur by Kyrgyz director Aktan Arym Kubat. A horse thief is not inherently a criminal, he frees horses — the patrons of the nomadic people from the shackles, releasing them to freedom. So here, a Mongol riding a Japanese city on a horse is a liberator of the spirit.

Well-played acting, musical, masterfully embodied directorial concept could not have become an absolute without unique culturally identifying frames of the free space of the steppe. This graphic juxtaposition of vastness on general plans and panoramas, and tightness on large cities, serves as a cinematic navigator, as a genre way of storytelling, and as a symbol of a peculiar cradle of a man framed by mountains.

The culture of nomads and the philosophy of Confucian Dao mixes wonderfully, crystallizing through synthesis a new concept of a person living under a turquoise sky. The sky in this philosophy is one for all. And celestial turquoise, in addition to direct linguistic reference to the Turkic beginning, is about granted happiness and prosperity. This is a return to the true value of man and unity with nature.

So what are all these films about returning home, about forgiveness and goodbye, about how difficult it is to understand and accept life? The themes of family and self-identification certainly unite not only the films analyzed above, but also many other films of the program of this festival. But these four are distinguished from the rest by perhaps the most important thing. They are about the love of life, about the love of cinema and sincerity.

By Alexandra Porshneva